Critical Mass Wins 2026 Independent Press Award

Critical Mass Wins 2026 Independent Press Award

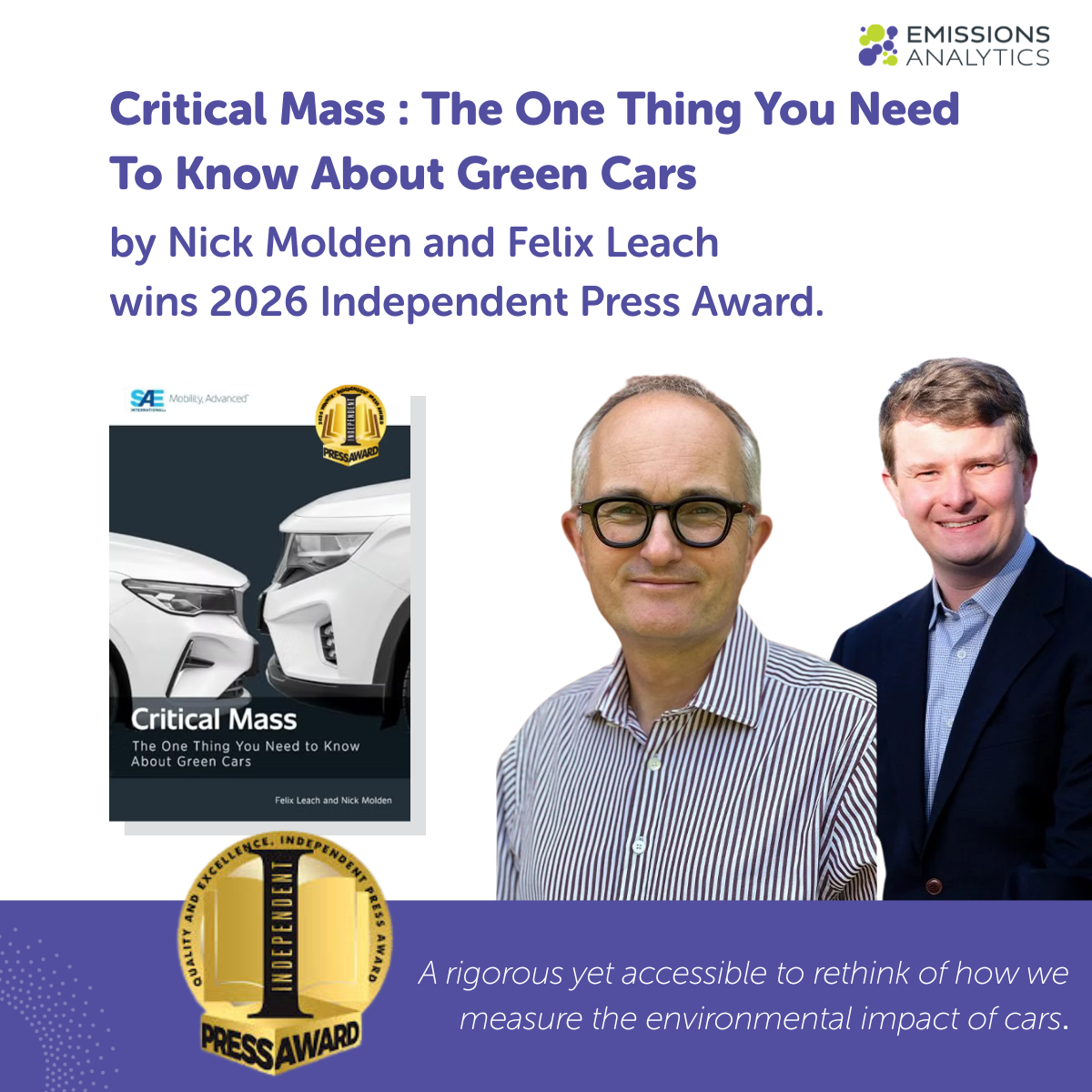

We are proud to share that Critical Mass: The One Thing You Need to Know About Green Cars has been named a 2026 Independent Press Award Winner.

In an era where climate change dominates global discussion, Critical Mass sees Felix our CEO, Nick Molden and Felix Leach unpack the complexity of vehicle emissions with clarity and rigour. Building on insights from Felix’s previous work, Racing Toward Zero, the book tackles the often-confusing landscape of automotive pollution by asking a deceptively simple question: what single piece of information best captures the true environmental impact of cars?

We are proud to share that Critical Mass: The One Thing You Need to Know About Green Cars has been named a 2026 Independent Press Award Winner.

In an era where climate change dominates global discussion, Critical Mass sees Felix our CEO, Nick Molden and Felix Leach unpack the complexity of vehicle emissions with clarity and rigour. Building on insights from Felix’s previous work, Racing Toward Zero, the book tackles the often-confusing landscape of automotive pollution by asking a deceptively simple question: what single piece of information best captures the true environmental impact of cars?

Written for a digital age awash with information but eluded of meaningful understanding, Critical Mass challenges oversimplified narratives around road transport and sustainability. Leach and Molden advocate for a more sophisticated, yet accessible perspective about emissions, examining the real-world impacts of different vehicle powertrains and moving beyond CO₂ alone to consider wider environmental and societal effects.

The Independent Press Award recognises excellence in independent publishing and honours books that demonstrate strong editorial quality, originality, and relevance. Being selected as a 2026 winner reflects the growing importance of transparent, factual analysis in climate and mobility discussions.

At Emissions Analytics, our work has always focused on delivering robust, independent data to inform policymakers, industry leaders and the public. This award reinforces the value of applying the same rigorous approach beyond research and into public-facing dialogue.

We would like to thank the Independent Press Award judges, Gabrielle Olczak from IPA, Sherry Nigam and SAE International for your support as publishers, our readers and everyone who has engaged with the book since its publication.

Find the full award listing here:

https://www.independentpressaward.com/2026-winners/9781468608212

Tyre Emissions & Sustainability USA 2026 agenda nears completion as ticket sales open

Industry leaders set to convene for critical discussions on tyre wear, regulation and real world emissions.

Emissions Analytics is proud to announce that the agenda for Tyre Emissions & Sustainability USA 2026 is now close to finalisation, with tickets officially available for purchase.

The conference will bring together regulators, OEMs, tyre manufacturers, material scientists and researchers to address one of the fastest-moving areas in transport sustainability. As non-exhaust emissions move firmly into the regulatory spotlight, tyre wear has become a defining challenge for the industry, with implications for air quality, environmental impact and vehicle design.

Industry leaders set to convene for critical discussions on tyre wear, regulation and real world emissions.

Emissions Analytics is proud to announce that the agenda for Tyre Emissions & Sustainability USA 2026 is now close to finalisation, with tickets officially available for purchase.

The conference will bring together regulators, OEMs, tyre manufacturers, material scientists and researchers to address one of the fastest-moving areas in transport sustainability. As non-exhaust emissions move firmly into the regulatory spotlight, tyre wear has become a defining challenge for the industry, with implications for air quality, environmental impact and vehicle design.

With the programme now largely confirmed, attendees can expect a technically rigorous agenda shaped around real-world data, regulatory direction and practical engineering pathways. Sessions will explore tyre wear particle emissions, test methods and measurement, material innovation, environmental impact, and how emerging standards are likely to shape future tyre and vehicle development.

The USA event builds on the established Tyre Emissions & Sustainability conference series, known for cutting through theory and focusing on evidence-based insight. The near-final agenda reflects growing industry urgency, with speakers contributing perspectives from across policy, research and commercial application.

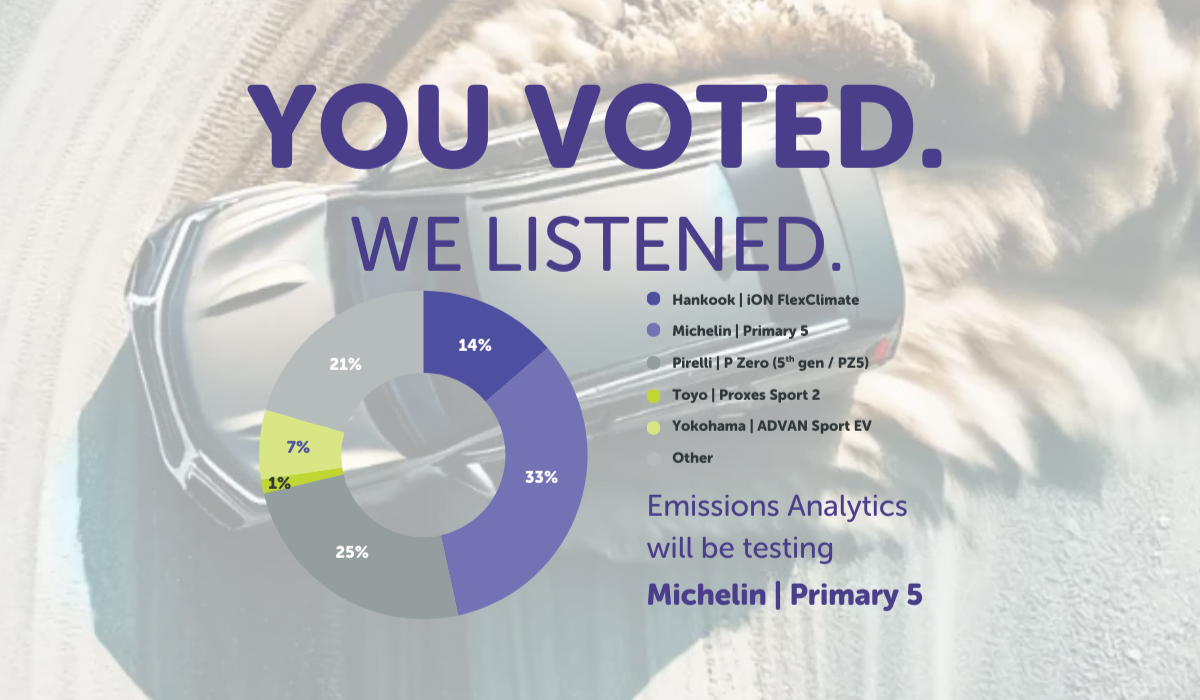

A major highlight of Tyre Emissions & Sustainability USA 2026 will be the exclusive first reveal of Emissions Analytics’ independent test results for the Michelin Primacy 5 tyre, selected by public vote, with findings presented live at the conference and not released elsewhere until after the European event.

Tickets are now on sale, with early booking recommended as interest continues to build across the North American market. Early bird pricing is now available for a limited time, offering discounted rates for those booking in advance, with this discount ending on February 7, 2026.

Further details on the agenda, speakers and registration can be found here.

About Emissions Analytics

Emissions Analytics is an independent global leader in real-world emissions testing and analysis. The organisation provides evidence-led insight across tyres, powertrains and fuels, supporting industry and policymakers with robust data to inform decision-making and regulation.

Governance Combustion Engine

Nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions are created in hot, high-pressure, oxygen-rich environments. Court 76 at the Royal Courts of Justice in London was certainly hot and high-pressure this week, albeit less oxygen-rich by the end of each session. Yes, the long-awaited “Dieselgate” group litigation case has kicked off in the UK, only ten years and 25 days since the scandal originally broke in connection with Volkswagen in the US. The case and damages may take a year to resolve, keeping the near-fifty lawyers in the room and others well serried and occupied. Notable by its absence is Volkswagen itself, though it casts a long shadow.

When authorities break their own environmental laws

Nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions are created in hot, high-pressure, oxygen-rich environments. Court 76 at the Royal Courts of Justice in London was certainly hot and high-pressure this week, albeit less oxygen-rich by the end of each session. Yes, the long-awaited “Dieselgate” group litigation case has kicked off in the UK, only ten years and 25 days since the scandal originally broke in connection with Volkswagen in the US. The case and damages may take a year to resolve, keeping the near-fifty lawyers in the room and others well serried and occupied. Notable by its absence is Volkswagen itself, though it casts a long shadow.

The case will hinge on whether a large number of manufacturers installed prohibited defeat devices in their vehicles to spot that they were underdoing a certification test and switch to a “cleaner” mode than used in normal driving conditions. There are many, nuanced, arguments on both sides. This may not, however, be the most interesting aspect of this case. That so many lawyers can be working for so long untangling the truth originally springs from a simple failure: a poorly and ambiguously written legal regulation. A legislative failure. Compounding this, in practice there was no routine surveillance to check that NOx emissions were actually low, and there was also no enforcement. Governmental failures. More troubling still, several authorities were aware of real-world NOx exceedances (4.5 times the limit according to Emissions Analytics’ independent testing, which had been published) and decided to do nothing about it, until they were forced to by the fall-out from Volkswagen being prosecuted in September 2015. Therefore, for at least five years, governments were happy for their own laws to be broken.

Sadly, this case is more commonplace than one would hope and expect. In fact, it is emblematic of a failed mode of regulation, government and enforcement that has become all too normal. We are not here talking about where an industrial company illegally dumps waste into a river and is then prosecuted by the competent authority. Rather, it is about governments enacting environmental laws or regulations that they then go on not to meet themselves. It is only because most offences are not criminal ones, or that public office comes with certain immunities, that many government ministers are not in jail.

For more than a decade, the UK government persistently breached its own legally binding air quality limits for nitrogen dioxide (NO2), in violation of both domestic and retained EU law. Under the EU Ambient Air Quality Directive 2008/50/EC, the government was required to ensure that NO2 concentrations did not exceed annual and hourly limit values after 2010. Yet successive administrations failed to meet these limits across dozens of urban zones, particularly in London, Birmingham and other major cities. The courts repeatedly confirmed this illegality: in landmark cases brought by Client Earth (2015, 2016 and 2018), the Supreme Court and High Court ruled that ministers had acted unlawfully by approving inadequate air quality plans and not delivering compliance “as soon as possible.” Despite judicial orders, updated plans again fell short of statutory duties under the Environment Act (1995) and the Directive, revealing a pattern of systemic non-compliance and policy inertia that left the UK in continuous breach of its own air pollution laws for much of the 2010s.

Also in the UK, the Environment Agency has repeatedly failed to monitor England’s rivers and groundwater for many emerging pollutants of concern, despite its statutory duty under the Water Framework Regulations (2017) to maintain comprehensive surveillance of water quality. While the Agency is legally required to track priority and specific pollutants to assess chemical and ecological status, its monitoring network has declined sharply over the past decade, with most sites now tested for only a fraction of relevant contaminants. Substances such as PFAS, pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and other persistent organic chemicals – widely recognised by scientists and regulators as major environmental and health threats – remain largely untested or are monitored only through limited pilot studies. This failure leaves large gaps in the national evidence base, undermines compliance with environmental targets under the Environment Act (2021), and exposes both ecosystems and communities to unquantified risks. The Agency’s narrow testing regime therefore represents a persistent breach of the precautionary and polluter-pays principles that underpin UK and international water law.

A third example relates to handling used tyres, where the “T8 exemption” is being used to undermine the UK’s environmental permitting regime by allowing large quantities of waste tyres to be treated and stored without the oversight, safety standards or accountability required under a full permit. Intended for small, low-risk operations, it has instead become a loophole exploited by commercial-scale processors, leading to widespread stockpiling, fires and illegal dumping. Bypassing the controls envisaged in the Environmental Permitting Regulations, the T8 exemption weakens enforcement, distorts the recycling market, and frustrates the original legislative intent to ensure that all waste activities are managed in a manner that protects human health and the environment.

Turning to wider environmental challenges, the Committee on Climate Change and the High Court have found that the UK government is in breach of its legal obligations under the Climate Change Act (2008, as amended) because its flagship strategy – the Carbon Budget Delivery Plan – fails to show how the legally-binding carbon budgets will be achieved. Ministers are said to have approved the plan based on incomplete and unjustified evidence, with key assumptions unsupported and no credible pathway provided for meeting future carbon budgets.

A final example relates to a recent study by Investigate Europe, which exposes a multi-level breakdown in the enforcement of soil and water laws across the EU: at the national level, several member states are failing to implement binding judgements from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on environmental protection, including cases tied to soil degradation and unlawful water extraction. At the supranational level, the European Commission – despite its role as “guardian of the treaties” – has allowed dozens of such rulings to sit unresolved for years without pressing for fines or binding corrective measures. For example, Spain has repeatedly ignored CJEU rulings over the illegal over-extraction of groundwater around the Doñana wetlands, a UNESCO-listed ecosystem now facing severe drought and biodiversity collapse. The result: key ecosystems continue to suffer, the rule of law is undermined, and the promise of enforcing EU soil and water standards remains hollow.

Generically, we can see that these breaches conform to a pattern. They all originally spring from a genuine environmental issue. It often goes wrong at the critical next stage, when a legislative or regulatory approach to solve the problem is postulated. At least five flaws can creep in. First, there can be over-ambition or scope-creep, often through public pressure or lobbying by environmental interest groups. Trying to solve too many problems at once leads either to parts of the rules being left incomplete or multiple leniencies or derogations being built in to reconcile the ambitions with practicality. It is even possible that industries to be regulated might act to expand the scope of a regulation, knowing it will then collapse under its own weight.

The next three flaws are legislative failures, often caused by asymmetries of skill, power and resource between regulators and the regulated. The second flaw is not including a robust method for on-going, independent, surveillance of the effectiveness and costs of the regulation. Thirdly, if no effective enforcement mechanism is included, there will be little force to the regulation and it will encourage non-compliance. Fourth, through a lack of technical skill or deliberate design, regulations get drafted ambiguously, which invites different parties to interpret in different ways – as the UK Dieselgate case shows.

Finally, also under public pressure or lobbying, a regulation might find its way onto the statute books despite the issue not being supported by the scientific evidence and, therefore, the application of the regulation imposes costs without provable benefit.

By some combination of these factors, the legally-enshrined environmental goals do not get met, or do not meet the public’s expectations. This is a recipe, at best, for public criticism, but increasingly likely it is an invitation for private legal action to be taken against governments for breaking their own laws. We are then in court, with all the attendant costs and time. Just the UK Dieselgate case is quoted as a “£6bn case.” While there is the monetary dimension, there is also the delay in dealing with the original issue, with all the associated societal damage. The combined result is that every time an authority is defeated in court, the lower confidence in authorities sinks and, often, decisions are then made to mitigate the negative effects that create unintended and undesired consequences – which can feed back to start of the process and create a doom-loop. In practice, what often happens is that governments are rapped over the knuckles and given more time to meet their own laws. This can happen repeatedly so the laws are technically still in place, but compliance may not be achieved in good time, if ever.

Is the US any better? At a high level, the US and Europe differ in how well they meet their environmental laws mainly because of variations in enforcement structure, political stability and regulatory culture. The US system relies on strong federal statutes, higher penalties and active private litigation, which encourage compliance but are undermined at times by sharp political swings. While agencies are arguably under-funded, their technical expertise often exceeds their peers in Europe. The UK and EU, by contrast, emphasise long-term, binding targets and the precautionary principle, but often struggle with weak or inconsistent national implementation and limited enforcement capacity.

Some might say that it is better to have some environmental regulation of a problem rather than none, even if it is imperfectly drawn, is not subject to surveillance and for which there is no realistic enforcement. However, this is the route we have been pursuing, and it has resulted in a significant loss of confidence in our governments’ ability to govern. As a constructive proposal, we should perhaps apply to environmental regulation similar principles to those used in making good tax policy, to create systems that are:

Cheap to establish and operate

As easy to understand as possible, without expert advice

Designed first and foremost by the regulator and not the regulated industry

Achieve the goal with the minimum collateral distortion in behaviour

Spread the cost of compliance as widely and thinly as possible

Ensure high legal certainty so players know the effects of changing behaviour

Have strong and well-understood surveillance and enforcement.

Unless changes like this are adopted, governments are effectively outsourcing good policy making to shifting alliances of activists, interest groups and the courts, in a way that is costly to society. In the meantime, to stop government passing laws they have no serious intention of fulfilling, we should enact the principle that any environmental regulation that is flouted by governments themselves for more than twelve months are automatically scrubbed from the statute books.

How, you may ask, is this relevant to the Dieselgate proceedings in the Royal Courts of Justice and whether vehicle manufacturers broke the law? Under the prevailing Regulation (EC) No 715/2007, Chapter IV, Article 13, countries of the EU were required to adopt “effective, proportionate and dissuasive” penalties for breaches of the Regulation. They did not do this, so authorities were breaking their own laws. Had they done what they had legally obliged themselves to do, which would have discovered any NOx exceedances quickly, we might not be sitting in a stuffy court room for months.

Nick Molden recognised as Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry

Nick Molden recognised as Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry. We are delighted to share that Emissions Analytics founder and CEO, Nick Molden, has been admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry (FRSC).

We are delighted to share that Emissions Analytics founder and CEO, Nick Molden, has been admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry (FRSC).

Fellowship is awarded to those who have made an outstanding contribution to the chemical sciences. Nick’s admission recognises his pioneering work to expand the boundaries of real-world environmental testing, particularly in relation to vehicle emissions, tyre wear particles and indoor air quality.

“This Fellowship reflects a commitment I made five years ago to build world-leading capability in analytical chemistry that could uncover the full environmental impact of vehicles. From tyres to fuels to air quality, we’ve developed original methods, filed patents and conducted over a thousand advanced tests to turn complex chemistry into meaningful action.” - Nick Molden

Over the last five years, Nick has spearheaded Emissions Analytics’ strategic expansion into analytical chemistry, with a focus on quantifying and communicating the real-world environmental impacts of vehicles and materials. This work includes developing novel methodologies for the chemical analysis of tyres, fuels, exhaust and indoor air, using advanced techniques such as two-dimensional gas chromatography and time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GCxGC-TOF-MS).

Critical Mass

Through this work, Nick is an author on many peer-reviewed papers, led the development of standardised test protocols and built a dedicated team of researchers and analysts. He continues to drive the company’s testing capability into new areas, including soil and water.

“By choice, I run a specialist team at Emissions Analytics. These specialists are picked not just for their skills but also their understanding of our mission to reveal real-world vehicle pollution.” - Nick Molden

In addition to his scientific work, Nick plays a leading role in public engagement. He is co-author of Critical Mass, a book written with Professor Felix Leach (University of Oxford), which presents a compelling case for using vehicle weight as a proxy for environmental impact. He has also given evidence to legislative bodies, including the UK Parliament and the European Parliament, while he also serves as an expert witness in major international legal cases.

Professor Felix Leach & Nick Molden FRSC

“I’m honoured to be admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry. This recognition reflects not only my personal journey into analytical science but the extraordinary efforts of the team at Emissions Analytics. By applying advanced chemical analysis to real-world problems, from tyre emissions to indoor air quality, we’re helping to reveal the hidden impacts of everyday products and push for constructive, evidence-based solutions.” - Nick Molden.

Nick holds an Honorary Senior Research Fellowship at Imperial College London and actively collaborates with more than 20 universities around the world. He is the founder and programme lead of the Tyre Emissions & Sustainability conference series in Europe and the US, which brings together global experts to share insights and solutions in this critical and emerging field.

From exposing diesel vehicle emissions during the ‘Dieselgate’ scandal to driving new standards for tyre testing and consumer diagnostics, Nick continues to champion independent science and constructive dialogue. His FRSC recognition reflects not only his personal commitment to evidence-based environmental improvement but also the growing importance of chemistry in addressing today’s most urgent air quality and sustainability challenges.

Emissions Analytics featured on SAE Tomorrow Today podcast

Emissions Analytics featured on SAE Tomorrow Today podcast.

Emissions Analytics founder Nick Molden and long-time academic collaborator Professor Felix Leach from the University of Oxford have been featured on SAE International’s flagship podcast, SAE Tomorrow Today.

The special episode titled ,Critical Mass’, marks the latest instalment of the series and explores one of the most pressing challenges in transport and the environment: how to measure, understand, and reduce real-world emissions.

Emissions Analytics founder Nick Molden and long-time academic collaborator Professor Felix Leach from the University of Oxford have been featured on SAE International’s flagship podcast, SAE Tomorrow Today.

The special episode titled: Why vehicle weight matters more than you think? marks the latest instalment of the series and explores one of the most pressing challenges in transport and the environment: how to measure, understand, and reduce real-world emissions.

Across the conversation, Nick and Felix discuss:

Why independent, real-world data is essential to move beyond assumptions in policymaking and regulation

The emerging evidence around tyre and road wear particles, and their impact on air quality and health

How measurement technology is evolving to capture a fuller picture of transport’s environmental footprint

What “critical mass” could mean for industry, regulators, and the wider public as pressure grows for cleaner, more sustainable mobility solutions

Hosted by SAE International, who are one of the world’s leading professional associations for engineering and innovation, the episode highlights the need for rigorous, transparent evidence at a moment when the global conversation around transport emissions is intensifying.

🎧 Listen to the full episode here: https://bit.ly/tomorrowtoday300

📽 Watch the promo clip below:

Looking in the right places: Real world tyre emissions

In this webinar, we explore:

Real-world data on tyre particles, leachates, and gaseous emissions

Emerging trends with EVs and budget tyres

How pollutants travel from roadways into rivers

Where monitoring and policy need to catch up

Our founder and CEO, Nick Molden and Dr Sasha Woods from Earthwatch Europe share data, fieldwork insights, and practical next steps for researchers, regulators, and industry.

In this webinar, we explore:

Real-world data on tyre particles, leachates, and gaseous emissions

Emerging trends with EVs and budget tyres

How pollutants travel from roadways into rivers

Where monitoring and policy need to catch up

Our founder and CEO, Nick Molden and Dr Sasha Woods from Earthwatch Europe share data, fieldwork insights, and practical next steps for researchers, regulators, and industry.

Tyre emissions aren’t just an air quality issue, they are showing up in soil and water too. And the science is evolving fast.

🎥 Watch the webinar here: Looking in the Right Places: Real-World Tyre Emissions

Grand theft auto?

No-one seriously doubts manmade climate change, and there is more of a scientific consensus on the range of likely effects than some of the more lurid headlines would suggest. The cost of the impacts is reasonably clear. To solve climate change, the technology options are also fairly clear and well costed. There is also consensus that we need to invest now in the solutions, even if there is some disagreement as to the total net cost over time. Why, then, is it all proving so hard to see through?

Why we are not solving climate change

No-one seriously doubts manmade climate change, and there is more of a scientific consensus on the range of likely effects than some of the more lurid headlines would suggest. The cost of the impacts is reasonably clear. To solve climate change, the technology options are also fairly clear and well costed. There is also consensus that we need to invest now in the solutions, even if there is some disagreement as to the total net cost over time.

Why, then, is it all proving so hard to see through?

We sit here around the societal dinner table shouting at each other, rather than genuinely discussing, listening and trying to understand each other. The carnivorous fossil fuel industry goads the vegan environmentalist, who moralises back, while trying to ignore the side-order of climate-denial fruit.

The simplistic answer to why this is proving a hard problem to solve is that there are powerful incumbent interests in fossil energy production and associated industries. That is not news, although it is an inescapable fact. We are stuck because we are trying to dislodge the vested interests in a way that is unlikely to work. We are attempting property appropriation, when we actually need to cut a deal. We are not on the brink of a political revolution because consumers remain quite happy with their cheap fossil fuels. Therefore, we need to address the preeminent position of the fossil fuel industry within our social contract, within agreed property rights and with the consent of all sides. After all, society needs industry for its security and quality of life, just as industry needs social acceptability.

If you think the accusation of property appropriation is far-fetched, consider this. Cars are a perfectly legal product for consumers to buy and use around the world, but in Europe, in particular, there have been progressively tightening constraints on when, where and how they can be used. Rules start sensibly, for example with speed limits and highway codes – the safety benefits outweighing the constraint on personal liberty. Access controls or pricing may deliver urban air quality benefits that society values. Then we get to blanket access prohibitions, technology bans, SUV-shaming and so on. For producers, who have equally been trading cars quite legally, they find technologies in which they have internationally competitive intellectual property (for example, internal combustion engines) banned, or assets they have developed (for example, oil fields) become stranded. It is reported that the European Union (EU) may even ban car rental firms and large companies from buying anything but electric vehicles from 2030.

To any pragmatic reader, the best answer is clearly to strike a midpoint that balances societal costs and benefits. All sides could probably agree on this, although sub-arguments would undoubtedly run as to where exactly that midpoint was. In practice what is happening is that each side is competing to extremes: net ZERO, vision ZERO, and so on. This is such a mistake as bads (such as pollution) tend to exist as by-products of goods (mobility). The only way to zero bads is zero goods. So, it is no wonder that the two sides cannot come together and just shout at each other, in a binary struggle for survival.

By virtue of their strong incumbent position, the fossil fuel industry can afford to take a cautious position on any significant changes. To try and dislodge these entrenched interests, the following playbook is often employed by opposing interest groups:

1. Highlight something undesirable (climate change, road safety), and make it an “emergency”

2. Set a target of zero for the undesirable thing

3. Make it a moral/existential crusade

4. Pick the winning solution

5. Pay “independent” organisations to lobby for your choice

6. Recruit followers and evangelists to pursue a grassroots campaign

7. Impugn the motives of anyone who disagrees with you.

Of the many questionable tactics, it is possibly stage two that is the most damaging. If you require zero bads then you ask for a de facto ban. You are appropriating physical and intellectual property. The constraint on free behaviour is not in proportion with the damage caused by the bad. Some car manufacturers promulgate the idea of zero fatalities from driving. As preventing those last few accidents will be so disproportionately expensive, it effectively makes cars infinitely expensive. A de facto ban. For society, undoubtedly an undesirable outcome.

The EU is undertaking a more direct form of property appropriation, but it also sits within the broader theme of net zero. It legislated recently to force car owners to scrap their vehicles when significant repairs are needed. Classic cars – typically valuable – are excluded but roadworthy older cars that deliver solid motoring but that are worth little in the market are highly vulnerable. We wrote about this “end-of-life” vehicle regulation when originally promulgated, in Kohlendämmerung.

Recent legislative discussions have made the proposal less troubling on the surface of it, but more troubling in the detail. Rather than being forced to scrap a vehicle at the point of repair, it only applies if selling the car, at which point proof of roadworthiness would be needed. In addition, sales between private individuals are excluded from the requirement. For vehicles being sold by or to a dealer, or via an online platform, a roadworthiness certificate would be required. Where a vehicle was in need of repair, showed excessive wear or had leaking fluids, an independent expert would need to be commissioned to opine on whether the vehicle was at the end of its life. At the end of life, the owner would need to deliver the vehicle to a special facility and obtain a certificate of destruction. As roughly half of vehicles in Europe are transacted commercially, rather than privately, this can be seen as a material transfer of value – in terms of expert fees – away from the vehicle owner, although you could always circumvent this by selling your car privately. Nevertheless, there would be inevitable diminution in vehicle value.

So, on the surface, the proposal has been made more acceptable and truer to the objective of avoiding exporting dud cars and aiding resource circularity. However, worrying terms hide in the details. It leaves it to Member States of the EU how strictly to implement the criteria listed in Part B of Annex I [of “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on circularity requirements for vehicle design and on management of end-of-life vehicles, amending Regulations (EU) 2018/858 and 2019/1020 and repealing Directives 2000/53/EC and 2005/64/EC.”] A country could take a pure and extreme interpretation of the “criteria to be assessed.” Worse, the European Commission can rewrite the criteria whenever it likes, without democratic safeguard:

In order to take into account technical and scientific progress, the power to adopt acts in accordance with Article 290 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union should be delegated to the Commission in respect of amending Annex I determining the criteria on when a vehicle is end-of-life vehicle.

If the sales of battery electric vehicles lag the key 2035 targets, what is there to stop the end-of-life rules being tightened both to put consumers off buying the last generation of internal combustion engine vehicles at the same time as pushing more existing vehicles off the road?

It is quite striking how far down the road of property appropriation we have already been led, but it has of course been done sliver after slice. Even so, it is not sufficient to criticise unless a viable alternative to solving climate change can be offered – but there is. As we have shown, aiming for zero bad entails banning the good. It’s going too far. Just to eke out that last benefit comes at a huge cost. The optimal point is, much more plausibly, the point at which the benefit increase equals the cost of achieving. This can only be practically achieved by putting a price, by some mechanism, on the pollution. In this vein, credit should be given to the EU for progress made so far on putting a price on carbon, although there is a long way to go to make the system broad enough in application to be effective.

For cars, there is fortunately a solution at hand, as detailed in a recent book by Professor Felix Leach and Nick Molden called Critical Mass – the one thing you need to know about green cars. As most unabated pollutants correlate well with car weight, if vehicle taxation were changed to be based exclusively on this factor, a price of pollution would effectively be established. No bans. No property appropriated. Just the driver paying the right price for the pollution created. The driver will adapt behaviour according to the price, and generate tax revenues to fund wider societal goods. As an aside, it is paradoxical that many who oppose such pricing approaches are strong advocates for dynamic pricing of electricity for electric cars.

To work out where you on the appropriation-pricing spectrum, ask yourself what the correct question is. Is it How do we limit driving? or is it How do we limit climate change?. The latter is the right question. If you plump for the former, you are using climate change to pursue a separate, car-restricting idea. And if you are plumping for the former, you will be much more disposed towards property appropriation. This polarity appears in another incarnation very often: How do we push electric cars? in contrast to How do we decarbonise transport?. They are not the same thing, and if you put the first question as the primary one, you are more interested in promoting electric cars than you are cleaning up transport.

Which brings us to the deal to be done to solve the problem of vested fossil fuel interests. Much as we might object to the pollution their products lead to, these companies have created legitimate, legal assets. Moving forward, their products should pay the true price of the pollution created, which is relatively uncontroversial, and is practical as described above. But this will still reduce the value of their assets, and, to get them to accept this, a level of compensation will be required. Not full compensation, though, as supporting decarbonisation will give them renewed societal legitimacy. Just as when the National Health Service was founded in the UK, the doctors were paid handsomely to forego their endowed interests to build a new public healthcare system. Just as when European slave owners were compensated for the loss of their labour to build a more equal society. This may be distasteful, but if an endowment is legally obtained, appropriating it will not work. This is also distinct from vexed discussion of compensation for past injustices, whether that is climate reparations, through first nation peoples, to the 245 cattle given to the Maasai for culturally sensitive artefacts in Oxford. Rather, we are talking about a conscious deal to allow progress.

In summary, then, we are not achieving our climate change goals because we have postulated zero as the desirable goal, have stirred up moral panic and are heading down the road of property appropriation. This will not work, not least because so many people have their pensions invested in industrial incumbents. There is a useful contrast with how so much progress has been made improving urban air pollution. Zero pollution has never been suggested, solutions have been carefully calibrated to balance societal benefit against cost, incumbent industry has been part of the solution, morals have largely been kept out of it, and air quality is much improved on just ten years ago. We need to apply this urgently to climate change. If it means net-minus-80% carbon dioxde and everyone plays their part in the solution, we will be a lot better off than now.

Yet it is so tempting for each of us to the decide the “right” solution and – due to the vital important of the topic – force this answer on others as a moral rather than objective imperative. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the French philosopher writing in 1762, believed that people, when acting rationally and considering the common good, would naturally choose to obey laws that promote the overall well-being of society. Forcing someone to adhere to such laws is, therefore, simply helping them realise their true, rational will. In the famous phrase, they should be “forced to be free.” This is very much the theme and philosophy of European governments right now. It is not so different from how Stalin and Mao sought “moral improvement” of their people. This is a slope, and a dangerous one if you choose to go down it.

So, we have a choice between an unpalatable deal and a dangerous challenge to liberty. Put another way: the combustion car is under threat of being outlawed in order to dislodge fossil fuel interests. The economic, geopolitical and social damage from this may be much greater than a pragmatic deal, and may just hand the economic rent enjoyed by fossil industries straight to a different set of equally uncontrollable industrial and political interests.

Chose thoughfully, and be careful what you wish for.

The most complex suicide note in history?

The 1983 UK General Election saw the Labour Party manifesto dubbed the longest suicide note in history. The current policy for decarbonising transport in the UK and Europe may be the most complex one. For the policy to work, it is necessary simultaneously to switch the grid to green sources and fundamentally change the relationship between consumers and their cars, in order to balance that new grid. Both are a major challenge, and if either fails, the whole policy fails. If it does go off plan, we may well end up with undesirable cars being powered by a dirty grid, and an unresolved climate change problem. Are industry and government locked in a suicide pact?

Vehicle emissions and grid decarbonisation

The 1983 UK General Election saw the Labour Party manifesto dubbed the longest suicide note in history. The current policy for decarbonising transport in the UK and Europe may be the most complex one. For the policy to work, it is necessary simultaneously to switch the grid to green sources and fundamentally change the relationship between consumers and their cars, in order to balance that new grid. Both are a major challenge, and if either fails, the whole policy fails. If it does go off plan, we may well end up with undesirable cars being powered by a dirty grid, and an unresolved climate change problem. Are industry and government locked in a suicide pact?

We are not used to living in age of electricity rationing, but this is a real prospect as we try to clean our grid with a big switch to renewable energy sources. The UK is already flirting with using its contingencies, even on the existing less intermittent grid, with fewer electric cars and data centres – although at no point so far has the grid come close to shutting down. On 3 December 2024, headroom was nearly eliminated such that a call for rapid reaction contingencies was initiated. On 8 January 2025, power had to be called from Norway to preserve headroom. These are just the first inklings of a problem, and one that applies to many European countries, not just the UK.

The underlying challenge is that we are trying to expand grid capacity to meet rising demand, while at the same time decarbonising it. The chosen primary route to decarbonisation is renewables – specifically wind and solar. These sources have two limitations. First, as they are intermittent, they need accompanying storage to save the surplus peak energy and release it during dark or windless hours. Second, they have relatively low “capacity factors” – the ratio of actual electricity generated in practice compared to the theoretical maximum. Therefore, it is necessary to “oversize” the installed capacity to generate the same electricity as traditional energy sources. Together, to make this approach work, it is necessary to install significant amounts of wind, solar and storage.

The UK’s National Energy System Operator (NESO), which runs the electricity grid, has published a number of scenarios for electricity demand and supply through to 2050, in the context of aiming for net zero . As a measure of the tightness of supply in 2050, even though the installed capacity of wind is forecast to increase by a factor of five and solar by a factor of six compared to 2023, this is not enough to switch off traditional fossil fuel production. Nuclear is also forecast to increase almost four-fold (which would be great for emissions reduction, but would need enormous commitment to achieve), and interconnections to other countries almost three-fold. Still, not enough.

To fulfil the projected 146% increase in annual electricity demand, the vehicle fleet is expected to contribute in two new ways: “demand management” and “vehicle-to-grid storage.” Demand management and its “smart pricing” seek to shift demand to times when there is surplus renewable power. Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) or bi-directional charging allows the grid to suck energy out of your car when the grid needs it. In other words, you will be constrained in when you can afford to charge up, and you might find a lack of charge in your car for your journey. If, for example, only 20% of cars are plugged in at the crucial time, those connected could lose 3 kWh each hour based on NESO projections. Of forecast peak capacity in 2050 of 119 GW, smart pricing reduces demand by 12 GW and V2G could provide 20 GW of power. Therefore, the vehicle fleet is expected to contribute 27% of peak demand to make the numbers add up. This comes at the cost of constraining personal freedom and the inherent attraction of the motor car. On most days, it will be fine, but consider those dark, still, winter Dunkelflaunten when your car will be an expensive brick. This will reduce the utility of a car, and so the willingness of consumers to pay. Fewer cars will be sold, at lower prices, with damage to the industry and personal welfare.

Some, however, would say that such an outcome would be good if it reduces demand for private motoring and leads to a shift to public transport. The bigger problem that remains is that, even with demand management and V2G storage, grid capacity might still fall well short of growing demand. Of the 116 GW of installed capacity in 2023, 36% of this is to be shut down to meet net zero – primary gas and biomass sources. If we take NESO’s “Electric Engagement” scenario where almost the whole fleet is electrified by 2050, 386 GW of installed capacity is needed. In other words, the “clean” part of the grid in 2023 would need to be increased more than five-fold by 2050. 344 GW of new capacity would need be installed that did not exist in 2023. Just 19% of the forecast grid in 2050 was already in place in 2023. Although the UK in particular has made good progress in decarbonising its grid so far, future infrastructure requirements for 2050 are large and risky. If, for example, we fall 25% short of the target for new build-out, it would leave a supply gap of 68 GW in 2050.

At the same time as we face the risk of falling short on supply, demand could rise more quickly than expected. This is not just speculation, as the question is being forced on us by a seismic change since the vehicle electrification policy was enacted: Artificial Intelligence (AI) is taking off in a way that exceeds the expectations of most. As a result, the well-understood increase in electricity demand needed to support a BEV fleet (around 28 GW in 2050 with unmanaged demand) has now been joined by rapidly growing – and somewhat unpredictable – demand from AI. Just one example, as reported in The Guardian recently, is an application submitted for a new data centre in the UK that would “…cause more greenhouse gas emissions than five international airports.” It is forecast to consume 3.7 bn kWh [3.7 TWh] of energy per year when running flat-out, releasing 857,254 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2), based on the current average grid mix.

The same NESO scenario as above assumes electricity demand from data centres to be 54 TWh in 2050. One of the more bullish forecasts is from the BloombergNEF, at 3,700 TWh globally. As the UK is approximately 3% of global GDP, that would imply 111 TWh in the UK. This would reflect 39% of 2023 demand and 16% of forecast demand in 2050. If correct, this would create 57 TWh, or almost 7 GW running constantly, of extra demand on top of the Electric Engagement scenario forecast. For comparison, Wood Mackenzie, a consultancy, is already tracking 134 GW of new data centres in the US, which would be 17 GW if pro-rated to the size of the UK. The BloombergNEF projection may, therefore, turn out to be cautious.

So, we can see that persuading customers to buy BEVs is only part of the challenge. Even if we electrify everything, our demand forecasts must be accurate, supply capacity build must happen, and car owners must be willing to engage with behavioural change. If these conditions are not met, we may not have the capacity necessary to meet demand. On plausible scenarios we could be at least 75 GW short, or 19% of the forecast installed capacity in 2050. In this case, what would happen?

The first instinct would be to “manage” demand further. The 75 GW shortfall assumes the maximum use of vehicle smart charging, so that is not an option. Authorities could move to a harder rationing of electricity for motor vehicles, which would be possible by restricting use of public chargers and more aggressive use of V2G storage capacity. It is likely that authorities would prefer to limit motor vehicle use than home heating or electricity, or industrial activities. With remote working now commonplace, driving would be the first activity to be cut, for all but essential purposes. The alternative would be to keep fossil fuel power generation going for longer, which would be politically highly embarrassing.

Despite the embarrassment, it is possible that governments may keep fossil power stations so people could keep driving. In this case, it would be fair to see vehicles as powered by marginal, “dirty” electricity. At present, the marginal CO2 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity is 350 in the UK, compared to an average carbon intensity of 124 g/kWh. So, almost three times dirtier at the margin. The European Union (EU) marginal rate is around 550 g/kWh, compared to an average of 244 g/kWh. In Poland, the values rise to 880 and 662 g/kWh respectively. This illustrates that the cleaner the average grid becomes, the greater the proportionate uplift at the margin is likely to be. It is worth noting that France’s current grid carbon intensity is 24 g/kWh on average but 510 g/kWh at the margin; even 18 nuclear power plants with 57 reactors is not always enough.

In future, the carbon intensity of the grid at the margin is likely to remain similar to today, at 350 g/kWh. Applying Emissions Analytics’ own real-world testing and decarbonisation modelling, we see the following. The second column covers all the up- and down-stream carbon in making and ultimately disposing of a vehicle, and liquid fuel production. The second column covers the tailpipe CO2 and the same emissions from electricity generation. Each powertrain/grid combination can then be compared over the life of a car compared to the gasoline ICE baseline.

The “average grid” scenario reflects the situation today, where there is sufficient grid capacity to power the new BEVs, but the sources of energy are mixed, including significant fossil fuel gas. The “marginal grid” scenario is similar to NESO’s Electric Engagement scenario, but where capacity growth falls materially short, vehicle-to-grid does not work, or demand growth is even greater than expected. In other words, the new BEVs are being powered entirely by the marginal, fossil fuel energy.

On the current grid mix, BEVs already reduce lifecycle CO2 by 49%, whereas in the EU it is only 32%. In the worst case scenario, having invested so much in electrifying the fleet, the UK might find only a 16% reduction in CO2 emissions. The EU could be in any even worse position, with CO2 rising by 13%, although this is unlikely to happen as the current marginal sources derived from coal would likely have been replaced by gas by 2050.

Which leaves an interesting dilemma. If we push ahead with a best case scenario that gives 85% CO2 reduction thanks to a clean grid, but we fail to make the grid work or demand soars unexpectedly, we could easily end up in a scenario that would be worse than the low risk option of converting the fleet first to plugless full hybrids, which would allow us to bank 29% CO2 reduction quickly and for low cost. Put another way: if we want to convert the fleet to all-electric by 2050, we must be certain that the grid can accommodate such a fleet cleanly.

The optimal strategy, we would suggest, is to push for hybridisation of the fleet simultaneously with grid decarbonisation, and only push on to fully electrified vehicles when the clean grid capacity is secure. This would be a more robust mix of risk and outcome. It would not meet net zero by 2050, but it would reduce delivery risk, and reduce CO2 more quickly in the early years by avoiding the high manufacturing emissions caused by largescale battery production. As readers of many previous newsletters will recall, Emissions Analytics believes that the data points to hybrids – especially full hybrids, with a decent battery size but no plug – being the best way to decarbonise transport for the next decade. After that, fostering technology-neutral competition between rival technologies would be optimal. During the coming decade, investment should be sharply focused on decarbonising the electricity grid, rather than subsidising well-off people to buy expensive (and heavy) pure electric cars.

If we mess this up, we might yet end up living the joke of having to charge up our electric vehicles with a diesel generator. (The AI-generated image above probably cost us 5 grams of CO2 emissions…) Having just recovered from a recent visit to an unnamed low carbon vehicle show that involved entering through unmistakable clouds of diesel fumes from the backup generators running the stands, this is clearly undesirable. At Emissions Analytics’ most recent conference, called Off-Highway Powertrain & Fuels and which we hosted in Chicago, a session stood about these static power sources. Demand is soaring for utility-scale, diesel-fuelled generators, most notably to power data centres to fulfil the already-voracious appetite AI systems have for energy.

Has the suicide note already been signed?

Postscript

We have taken a largely UK and European perspective in this newsletter, but similar arguments are playing out in the USA. For an insightful read from that perspective, we would recommend the article U.S. Energy Policy Undercuts EVs to Make Way for AI by Tammy Klein published recently in Transport Energy Strategies.

Emissions Analytics supporting citizen science in air and water

Inspired by two recent projects, Emissions Analytics is pleased to announce its support for the launch of a new service to empower citizens in testing their air and water: WHATSINMY?.

Inspired by two recent projects, Emissions Analytics is pleased to announce its support for the launch of a new service to empower citizens in testing their air and water: WHATSINMY?.

This will put the power of advanced laboratory techniques into the hands of any citizen interested in, or concerned about, their quality of their water or air.

The aquatic inspiration for this was a project led by Earthwatch Europe that sent people out around the south east of England to take samples of river water. Emissions Analytics’ contribution was in identifying the hallmark chemicals of tyre wear emissions. Chemicals from styrene to 1,4-Benzenediol, 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) were identified in road run-off flowing into rivers, and we were able to identify that they are likely to have originated from tyres. This was made possible by Emissions Analytics’ database of 500 chemically reverse-engineered tyres currently on the market.

The work has already been expanded as part of Earthwatch’s Great UK WaterBlitz programme, and you can see the very latest results here. The rivers of the Evenlode catchment had 995 unique organic chemicals, 592 of which appear in Emissions Analytics’ tyre chemicals database. Of those, 41 are mentioned in academic literature as coming from tyres, but a further 11 were in all of the river samples and we are confident are in tyres, but have not yet been studied in the literature.

On the other side of the Atlantic, late 2024 also saw the launch of major new project testing air quality samples, this time in Southern California for the South Coast Air Quality Management District. Emissions Analytics has been commissioned to run a multi-year project testing hundreds of air samples. Again, the main aim is to identify chemicals originating from tyres, again harnessing our tyre reference database.

Both these pieces of work involved the sophisticated laboratory equipment run by Emissions Analytics called two-dimensional gas chromatography and time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Sounds a bit baffling, but this is a specialist piece of kit that allows you to take a sample and separate out all the organic compounds in the mixture, identify them and quantify the amount one by one. Of the hundreds compounds we find in a sample, each can have radically different effects, from being harmless to highly toxic.

This all led to the inspiration for WHATSINMY?. Why not put this power into the hands of citizens, at a time when there is great concern about water and air quality? There is a loss of trust in governments and regulators to protect us. Dieselgate collapsed confident in vehicle and air pollution regulation. Rivers regulated tainted with effluent has led us to doubt the ability of regulators to contain the behaviour of industry.

So, Emissions Analytics is now committing to providing this sophisticated laboratory testing equipment to anyone who is interested. We will be supporting citizen science campaigns to collect water and air samples. To complement that, WHATSINMY? offers the ability to buy personal test kits directly on its website. This can be used in your home or office to diagnose private contaminations concerns, as well as to detect pollutants in public spaces: unleash the power of expert testing science in your world.

Emissions Analytics has always been committed to understanding and reducing real-world emissions, and is excited to support the democratisation of its work to solve the pressing pollutant issues of 2025 and beyond.

New frontiers in understanding tyre emissions: Ultrafines, smog, VOCs and PFAS

Nick explores the latest areas of research on tyre emissions, with a particular focus on tyre wear, ultra-fine particles, and gaseous emissions and dives into the complexities of tyre emissions beyond particle mass, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and emerging concerns such as PFAS presence in tyres.

In this presentation, Nick explores the latest areas of research on tyre emissions, with a particular focus on tyre wear, ultra-fine particles, and gaseous emissions and dives into the complexities of tyre emissions beyond particle mass, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and emerging concerns such as PFAS presence in tyres.

Our findings, including recent studies on ultra-fine particle dispersion and tyre composition analysis, shed light on the environmental impact of mobility and the pressing need for a holistic approach to sustainability.

Critical Mass 4: The Politics - Molden & Schmidt Episode 15

We've heard about the big idea - taxing cars by weight and mileage, not engine type. We've looked at the science, the money, and the practicalities? But what about the politics? What could persuade governments to revolutionise the vehicle taxation system? How could this concept overcome the scepticism of the press, public, and politicians who don't like meddling in the costs of driving? Those are the big questions we explore in this final episode of series 2.

You can also listen here…

Spotify

Critical Mass 3: The Money - Molden & Schmidt Episode 14

So how would this radical new system work in practice?

How much would motorists actually pay?

Would petrol still be taxed, too? And could you cheat your way around it?

Those are the questions Nick and Felix set out to answer in episode three of our second series. Their new book - Critical Mass - explores the concept of taxing cars by weight and miles driven, not by type of engine. Oliver's here to 'stress test' their proposition, and see if their answers really stack up.

Critical Mass 2: The Science Molden & Schmidt Episode 13

In the last episode, Nick and Felix pitched their big idea - to tax cars by weight, not type of engine. They say mass is the critical environmental factor, in an electrified world of motoring. But what's the science behind it? Do the sums and formulae add up? That's the subject of this second podcast of series two.

We're joined again by Felix Leach, Associate Professor of Engineering Science at the University of Oxford. He and Nick are the authors of a new book - Critical Mass: The One Thing You Need to Know About Green Cars.

And Oliver's on hand, too - to put Nick and Felix through their paces.

You can also listen here

Reimagining car taxation: a sustainable approach to motoring

In this episode of Molden & Schmidt - Nick and Felix Leach introduce a groundbreaking concept in sustainable transportation: taxing vehicles based on their weight and miles driven.

In this episode of Molden & Schmidt - Nick Molden, CEO of Emissions Analytics, and Felix Leach, Associate Professor of Engineering Science at the University of Oxford, introduce a groundbreaking concept in sustainable transportation: taxing vehicles based on their weight and miles driven.

Drawing from their new book, Critical Mass: The One Thing You Need to Know About Green Cars, Nick and Felix explain how this approach could transform motoring sustainability while aligning with governments' revenue needs.

The conversation explores the mechanics of this proposal, exploring its potential impacts on drivers, policymakers and the automotive industry. With Oliver asking the tough questions, Nick and Felix break down how this model could work in practice and why it might be the key to harmonising environmental and economic priorities.

Also available on:

Podcast Feature: Building Better with Brandon Bartneck

In the latest episode of Building Better with Brandon Bartneck, Nick Molden and Felix Leach explore the future of sustainable transportation.

In the latest episode of Building Better with Brandon Bartneck, Nick Molden, CEO of Emissions Analytics, and Felix Leach, Associate Professor at the University of Oxford, explore the future of sustainable transportation.

The discussion highlights the pivotal role of two key factors—mass and distance—in determining the environmental impact of transportation. Nick and Felix emphasise the importance of these variables as cornerstones of sustainability.

They also advocate for a transformative reset of public policy and taxation systems, calling for simplified frameworks that align with environmental realities. Exploring the interconnected transportation ecosystem, the influence of consumer choices and actionable steps toward a greener future, this episode offers valuable insights for anyone passionate about sustainability.

Tyre emissions: analytical testing of 6PPD and its alternatives, and identifying emerging compounds

Our latest webinar exploring the cutting-edge science behind tyre emissions and the growing concern around 6PPD – a key chemical preservative found in tyres. This session explores the analytical testing processes used to uncover the presence of 6PPD and its alternatives, shedding light on how these compounds impact the environment and what the future holds for tyre manufacturing and sustainability.

Our latest webinar exploring the cutting-edge science behind tyre emissions and the growing concern around 6PPD – a key chemical preservative found in tyres. This session explores the analytical testing processes used to uncover the presence of 6PPD and its alternatives, shedding light on how these compounds impact the environment and what the future holds for tyre manufacturing and sustainability.

In this webinar, you’ll discover:

The role of 6PPD in tyres and why it’s under increasing scrutiny.

Our analytical testing methods, including real-world sampling and lab-based evaluations.

Insights from over 500 tyre tests across the US and Europe.

How electric vehicles are accelerating the tyre emissions challenge.

Emerging alternatives to 6PPD and the potential for reducing environmental impact.

This webinar is essential viewing for policymakers, tyre manufacturers, sustainability professionals, and anyone interested in the intersection of automotive technology and environmental health.

Watch the full webinar below and stay ahead of the latest developments in tyre emissions and sustainable transportation.

Nick Molden on BBC Breakfast – Critical Mass in the Spotlight

Our founder, Nick Molden, recently appeared on BBC Breakfast to discuss his new book, Critical Mass. In the interview, Nick shares his views on the future of transport and why he believes cars should be taxed based on their weight and the miles driven.

Our founder, Nick Molden, recently appeared on BBC Breakfast to discuss his new book, Critical Mass. In the interview, Nick shares his views on the future of transport and why he believes cars should be taxed based on their weight and the miles driven.

Discover more about Nick’s insights and how Critical Mass is sparking important conversations about sustainable transport and policy.

The impact of road-tire wear: a hidden source of airborne microplastics and black carbon

Recent studies conducted in the Colorado Rocky Mountains reveal that tire particles, laden with nano-sized carbon black, are being deposited on high-altitude snow, contributing to accelerated melting and atmospheric warming. Analysis by Emissions Analytics identified organic compounds in these particles that match those found in road tires, highlighting their widespread environmental presence.

A major source for airborne microplastic particles is road-tire wear. Microscopy and chemical analyses of wind-blown particles on dirty, high-elevation (2865-3690 m) snow surfaces in the Colorado Rocky Mountains revealed the presence of black carbonaceous substances intimately mixed with microplastics, particles interpreted as tire matter.

Identical and similar particles occur in shredded tires and in samples collected from road surfaces. The black substance responsible for the black color of all tire particles is nano-size carbon black, a tire additive that homogeneously permeates tire polymers and other additives and that strongly absorbs solar radiation .

The key to documentation of worn tire matter was the identification in two-dimensional gas chromatography by Emissions Analytics of many organic compounds in snow common to those in road tires. The mass of black carbonaceous particles produced by road-tire wear may be estimated by multiplying measured mass of eroded tire-per-distance traveled by vehicular distances. The eroded tire mass from moving vehicles used for these estimates was measured by Emissions Analytics.

Under assumptions of amounts of tire-wear particles emitted to the atmosphere, the mass proportion of atmospheric black carbonaceous matter from annual road-tire wear might be as much as about 10-30% of atmospheric black carbon, such as soot from vehicle exhaust and domestic cooking. Black particles from road-tire wear may thus be an important component that contributes to melting of snow and ice as well as to warming the atmosphere. The potential toxicity of organic compounds in black-tire matter is another concern for the health of organisms in mountain ecosystems. A revised estimate for the annual mass of eroded tires globally is 6550 kilotonnes.

Citation:

Reynolds, R. L., Molden, N., Kokaly, R. F., Lowers, H., Breit, G. N., Goldstein, H. L., Williams, E. K., Lawrence, C. R., & Derry, J. (2024). Microplastic and Associated Black Particles from Road-tire Wear: Implications for Radiative Effects across the Cryosphere and in the Atmosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 129, e2024JD041116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JD041116

Emissions experts call for reform of car taxation to be based on a combination of weight and mileage

· Simpler car tax system proposed, based on vehicle weight and miles travelled

· Would apply the ‘polluter pays’ principle

· Switching to 150 kg lighter car or driving 1,000 fewer miles will save £100 a year

· Experts call current VED system ‘a mish-mash of incentives and penalties’

Cars should be taxed on a combination of weight and mileage, according to a radical new study from emissions experts Nick Molden and Felix Leach.

Molden, who is the CEO of emissions testing company, Emissions Analytics, and Leach, Associate Professor of Engineering Science at the University of Oxford, will be launching their new book: Critical Mass: The One Thing You Need to Know About Green Cars at Keble College, Oxford, on November 25th and Imperial College, London, on December 2nd. The events will outline proposals for a simpler, more environmentally-credible road tax system.

The launch of the book will be hosted by Chief Executive of the RAC Foundation and former Director General at the Department for Transport, Steve Gooding, and Professor Gautam Kalghatgi, until recently Visiting Professor at the University of Oxford.

The book outlines in with brutal clarity that the current system for Vehicle Excise Duty (VED) is flawed, even calling it a ‘mishmash of incentives and penalties’.

The result is a powerful evidence-based thinking that has the basis to overcome bitter factional disputes between different groups trying to promote one powertrain over another. Former Secretary of State for the Environment and Deputy Prime Minister, Michael Heseltine, said: “I welcome this contribution to the most important challenge of our time.”

It is a timely release. Next year the so called ‘road tax’ will undergo a major overhaul and it will include Electric Vehicles (EVs) that are currently exempt from VED.

Starting April 1st, 2025, EVs will lose their VED exemption, however. That means buyers of new EVs will have to pay the next lowest first-year tax rate, which currently stands at £10. Once an EV hits its second year on the road, owners will be required to pay the standard VED rate, which is currently £190 and is expected to increase with inflation from April 2025.

The new legislation will also hit buyers of EVs costing over £40k with additional tax and used EV buyers and hybrid buyers will also have to pay more.

But Molden and Leach say there is a solution that is not only better for the environment, but simpler to administer and much easier to understand.

Molden explained: “Taxing a car on a combination of its weight and mileage offers a simple, potentially universal approach to pricing-in the environmental impact of cars while at the same time overcoming the objections to the current mish-mash of incentives and penalties.

“In our book, we offer an intuitive ‘proof’ of why mass and distance are fundamental to designing a system to incentivise the purchase of ever-greener cars and this is contrasted with other flawed bases for judging environmental impact, such as measures of vehicle efficiency, including energy and fuel efficiency, as well as elements incorporated in the current system such as fuel type and laboratory carbon dioxide emissions.”

The two experts outline ways in which the system can be adopted and show the types of cars likely to taxed lightly and those that will be more expensive to keep on the road. Broadly, smaller cars will be cheaper to tax.

Under Molden and Leach’s proposed system (taking the example of the UK) if an average car is 150 kg lighter or does 1,000 fewer miles, the owner would pay £100 less per year.

“Specific tax rates are proposed and compared to existing taxes to illustrate winners and losers – winners being small city cars and loser including high-mileage heavy cars and SUVs,” explained Leach. “The concept proposed is a reliable revenue-raiser at a time of widespread fiscal pressure and declining vehicle taxation. It could also be adopted rapidly and transitioning to it is easy.”

The idea of taxing a car on the basis of its weight and miles travelled, also translates easily for a car-buying public that has to negotiate confusing rates and inconsistencies, while car makers have increased the size and weight of their models with impunity.

Molden added that deploying a single measure of a car’s environmental credentials to guide purchases and government policy is the way forward, and the measure that takes account of approximately three-quarters of the environmental impact of a car is the car’s weight, and that metric correlates well with environmental damage.

Molden added: “Most people want to do the right thing environmentally when they are buying a car, but the information and choices are now too complex for any normal consumer to understand fully. The question was whether there is a simple, practical way to point the car buyer in the right environmental direction and allow governments to tax and subsidise the right things – and there is.”

Ends

Notes to editors:

Nick Molden is the Chief Executive Officer of Emissions Analytics (https://www.emissionsanalytics.com) and a Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Imperial College London

Felix Leach is Associate Professor of Engineering Science at the University of Oxford (https://eng.ox.ac.uk/people/felix-leach/)

Critical Mass: One Thing You Need to Know about Green Cars is now available in hard copy and as an ebook. To obtain a copy go to: https://www.sae.org/publications/books/content/r-575/ or https://amzn.eu/d/2FrpYUH.

To apply for tickets to the launch events, please email info@emissionsanalytics.com.

Kohlendämmerung?

Twilight of the carbon economy

Dusk approaches, but the denouement is unclear. Will the flames of 2026 engulf fossil fuels, the internal combustion engine, electric vehicles or net zero? Are we about to see the twilight of the carbon economy? Or perhaps twilight of our environmental idols?

Twilight of the carbon economy

Dusk approaches, but the denouement is unclear. Will the flames of 2026 engulf fossil fuels, the internal combustion engine, electric vehicles or net zero? Are we about to see the twilight of the carbon economy? Or perhaps twilight of our environmental idols?

The clever construction of zero emission vehicle mandates and the exclusion of manufacturing emissions from the definition, has created a scenario where European authorities apparently must triumph in their push for electrification of new vehicles, whether it actually reduces carbon dioxide emissions sufficiently. The battle has now moved to second-hand cars. To meet net zero by 2050, it is a priority to get all internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles off the road, just as those drivers for whom battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are not suitable hold onto their ICE cars as long as they can. Although car drivers are repeatedly assured by governments and their funded spokesmen that no-one will appropriate their existing ICE vehicles, current drafting of EU legislation suggests otherwise. While it remains controversial whether they are coming after your ICE car, let us examine the question of whether such a policy could be justified by any emissions reduction it would bring about.

Before going further, this topic has previously generated controversy, when it was wrongly reported that new legislation proposed a ban on repairing cars over 15 years old. This was rightly debunked by AFP. Even though no such time limit was proposed, there is genuinely good motivation in stopping unroadworthy vehicles in Europe being exported to countries with lesser standards. However, is there further nuance in the proposed regulation, and how does it square with emissions reduction?

To incentivise low carbon dioxide emission vehicles into the market, Europe – with some minor differences between the European Union and the United Kingdom – use three main tools. First, and most high profile, is the ‘zero emission vehicle’ (ZEV) mandate, which requires a certain proportion of each manufacturer’s new car sales in a year effectively to be BEVs. Second, there are the fleet average carbon dioxide targets, also applied to each manufacturer, and which are in practice similar to the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) targets in the US. Weighted by sales, their emissions each year must be below a certain threshold set by the EU. The third and least visible tool, is the very definition of BEVs, along with hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, as emitting zero carbon dioxide, which creates a large hidden bias in their favour. This is clearly untrue during their usage – as the electricity to power them in almost all cases emits some carbon – and during their manufacture. On average, a BEVs emits around six tonnes more carbon dioxide when it is made compared to an equivalent ICE vehicle, but then emits around 1.5 tonnes less each year during its use. As this zero emission definition feeds into the requirements of the ZEV mandates and CAFE targets, all three can be seen to work in harmony to create a strong incentive for manufacturers to sell BEVs, and an incentive that is stronger than is warranted by the emissions reduction potential.

Despite these incentives, only about one in five new car buyers in Europe are opting for BEVs, which is a flattering proportion as the size of the market remains subdued, in part due to some people switching to buying used having been priced out of the new market as manufacturers have rationalised their traditional vehicle ranges. Nevertheless, authorities will be able to force through their BEV targets because manufacturers can simply ration the availability of ICE vehicles. As CAFE targets and ZEV mandates are based on market share by technology, if manufacturers are struggling to sell BEVs, they can always restrict ICE vehicle numbers. To match supply to demand, this would be done by increasing ICE vehicle prices and consequently their per unit profitability. Manufacturers would let governments and authorities take the heat for factory closures and lost jobs as a result of lower vehicle sales volumes. The alternative scenario is that governments ply the industry with BEV subsidies to boost their sales volumes, thereby maintaining ICE vehicle sales volumes too. This is less likely, however, as most governments are fiscally constrained, and such subsidies would primarily act as significant financial transfers to industry.

The lack of desirability of BEVs is most vividly seen in their current depreciation rates. In the first three years of life, a typical BEV in Europe loses around half of its value. In cash terms the reality is starker, as a typical BEV is more expensive than the equivalent ICE vehicle, so the cash depreciation can be over 50% more for the BEV. So long as this demand remains weak, the effective price of new BEVs will remain higher, thereby limited the quantity sold. At the same time, the second-hand value of ICEs vehicles is strong – up 21% in Europe since the start of 2020, according to EUROSTAT – through some combination of consumers switching from new to used vehicles and a general rising demand for car transportation. As ZEV mandates get tougher, this trend is only likely to strengthen. Existing owners of used ICE vehicles will be incentivised to hold and maintain them for longer than before, while those who would previously have bought new will enter the market for used ICE vehicles. For a long time, demand for BEVs may remain weaker than governments wish due to the presence of a preferable alternative.